Companion Planting

Part Nineteen of the Vegetable Patch from Scratch Series

The idea behind companion planting is that some species of plants grow better in the presence of others. That is, planting them near each other may result in positive impacts for one or both of the plants. These may include:

Increased yield

Better flavour

Protection from pests

Better use of nutrients

There are plenty of lists and advice about what makes good companions in the garden. One example often cited is that growing basil and tomatoes together improves the flavour of the tomatoes. In my experience, the choice of tomato variety has more impact on flavour than any nearby growing basil.

There’s also plenty of advice about “bad companions”: tradition has it that you should avoid growing tomatoes and potatoes near strawberries. This is because tomatoes and potatoes can be hosts for verticillium wilt, which could spread to your strawberry crop. This is a risk, but we can’t grow all of our plants in isolation. There’s just not enough room!

I take the approach that there are not really any bad companions in the garden, as discussed in my last post. I practice crop rotation based only on the nutritional requirements of the crops I am growing. Healthy soil, combined with disease-resistant plants, should protect most of my crops better than companion planting or crop rotation ever would.

Start seeing your garden as an ecosystem

I don’t worry about specific rules of “what goes with what”. Instead, I focus on diversity and creating a healthy garden ecosystem. This ensures that pest populations such as aphids are kept in check by predators such as ladybirds. The diversity provides a haven for wildlife, reduces the need for chemical sprays and provides a range of food for my family to eat.

Diversity equals resilience!

Flowers are the single most important thing you can introduce to your garden to make it more resilient

For example, lacewings are beneficial in the garden because they eat aphids and whitefly. But if lacewings eat aphids, not flower parts (pollen or nectar), why would flowers bring good bugs into the garden?

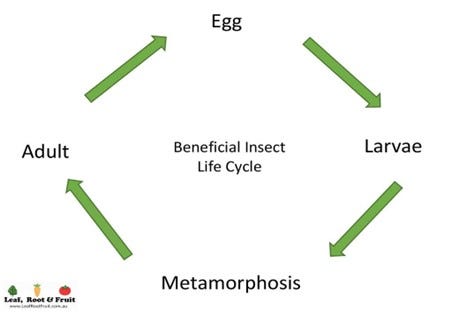

To find the answer, we have to understand the life cycle of beneficial, or predatory, insects.

Let’s start with an egg that hatches into a larva. In the case of the lacewing, it is an antlion. It is the antlion larvae that do all of the good work in the garden.

The lacewing antlion eats 60 aphids a day! Ladybird and hoverfly larvae consume a similar quantity of pest bugs. This tends to be the stage of the beneficial insect life cycle that does the pest control in the garden for us.

The next stage in the life cycle is metamorphosis. Butterflies, lacewings, ladybirds and hoverflies all create a cocoon or a chrysalis and go through a metamorphosis. At the end of this transformation, they emerge as adults with wings.

The adult insect does not usually eat “bad bugs”; instead, it usually eats pollen.

Pollen comes from flowers. So, if we don’t put lots of flowers in the garden, the adults (who now have wings) will fly away to find pollen.

The next stage in the life cycle is the laying of eggs. This is likely to take place near something that all stages of the life cycle, from larvae to adults, can use as a food source. So, if you don’t have “bad bugs” and pollen present in your garden, the beneficial insects will lay their eggs elsewhere, probably in your neighbour’s garden, where they have both types of food available.

The eggs hatch in your neighbour’s garden. But the larvae don’t have wings. They stay there, helping to keep your neighbour’s “bad bug” population in check. Without flowers you won’t have that army of good bugs in the garden ready to control any “bad bugs” and keep them in balance.

The good bugs need food for every stage of their life cycle. That means flowers for the adult stage and sap-sucking insects for the larvae stage.

Good bugs can’t exist without bad bugs

You can buy good bugs from some online retailers, or use pheromone lures to bring beneficial insects into the garden. But what’s the point in attracting them in if you don’t have the food for them? It’s time to plant some flowers in your garden!

Flowers you might want to include in the vegetable patch include:

Borage

Calendula

Chamomile

Cosmos

Marigolds

Grow flowers in your vegetable patch to attract beneficial insects. From left to right: Borage, calendula, chamomile, cosmos and marigold.

Let your vegetables flower

Let your vegetables go to seed for the benefit of the insects. Don’t rip them out of the ground as soon as they bolt. An added bonus is that you’ll have the next crop of vegegetables self-sown, for free and with no effort whatsoever. Great plants to let self-seed in the vegetable patch include parsley, dill, fennel, lettuces and carrots.

Want to know more about building resilient garden ecosystems?

I’ve put together an extensive series of posts about this topic. See the following for more information:

Pest predator dynamics and balance

Attracting beneficial insects into the garden

How to turn your garden into a resilient ecosystem

This post is free to help spread the word about creating resilient ecosystems and reducing pesticide use. Please share it widely.

This post is one of many in my gardening series Vegetable Patch from Scratch. See the series index for a list of other topics in the series.

Read the next post in the Vegetable Patch from Scratch series:

PART 20: Vegetable patch layout and spacing