My kids love helping me in the garden. One of their favourite activities is growing potatoes. Potatoes are a very easy crop to grow, and planting tubers is much easier for little fingers than carefully sowing tiny broccoli seeds.

Once planted, potatoes are quick to emerge from warm soil. This quick turnaround keeps children engaged. The flowers are bee magnets and together we enjoy tracking the insects’ flight path as they come and go from the hives. But the fun really begins when the tubers develop. Bandicooting for potatoes (see the note at the end of this article) or digging them up is a delight for kids. It’s like the end of a treasure hunt where you finally get to dig where X marks the spot.

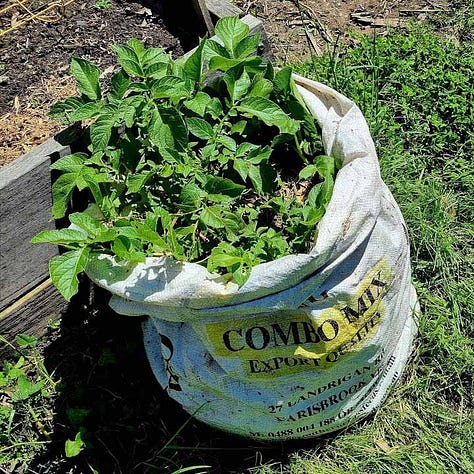

Potato towers, grow bags, sacks and small spaces

Potatoes make up a big portion of our household diet and we grow a lot of them. But you need only a small space and you can grow a few potatoes. You’ve probably seen plenty of social media posts about different ways to grow potatoes. Folks have created some fancy set-ups.

One set-up I would avoid, though, is a potato tower constructed out of car tyres. Car tyres can leach some nasty chemicals as they break down. I don’t believe they belong anywhere in the garden (or playgrounds).

Common problems when growing potatoes

Potato leaves are sensitive to frost, so planting too early might cause a bit of dieback in the leaves, but the plants usually recover if the frost wasn’t too severe.

I usually leave my spuds in the ground for as long as possible and just dig them up as required. Our winters are very wet, and I find that some varieties of potatoes are more prone to rotting in the soil than others. Either choose your varieties carefully (more on that later) or dig them up before the soil becomes too cold and wet.

My biggest problem when growing potatoes is forgetting to keep the tubers covered. In the height of summer, the plants do a great job of shading any tubers that are developing on the soil surface. But as the plants grow taller, they start to lean over. This allows gaps to form in the canopy. As autumn nears the plants often begin to die back and soon all the shade is gone.

Soil or compost needs to be mounded up against the stems of the plants to cover developing tubers and stop them turning green. I am always too busy or forget to undertake this important task. The result is that around a third of our potatoes come out with green on them. Fortunately, many tubers develop deep down and remain covered until we dig them up. I’ve noticed that some varieties are more likely than others to develop tubers on the soil surface and some are better at keeping them covered. More on that in the list of varieties at the end of this post.

The following posts in the Vegetable Patch from Scratch series will give you more information on:

Myth-busting: Eating green potatoes will kill you

Once exposed to direct sunlight, potato skins will begin to develop a green colour and a toxin called solanine. It’s important to note that the green is caused by chlorophyl, but the same conditions that induce chlorophyl formation also induce formation of the solanine toxin. The increase in the two is correlated but not caused by one or the other.

Solanine toxin in green potatoes can cause digestive issues, but it takes a lot of it to cause death. It is incredibly rare for someone to die from eating green potatoes but it’s best to avoid eating them anyway. Instead, I use any affected tubers to plant next year’s crop.

Read more about storing potatoes here.

The nitty-gritty of growing potatoes: phenology, varieties and planting

Timing

This chart shows the best times to grow potatoes based on my experience of growing these crops in both Melbourne (warm temperate) and Kyneton (cool temperate), both in south-eastern Australia. The timing is applicable for growers in the same climates across the southern hemisphere. Northern hemisphere folks will need to adjust the timing by six months.